“Steve! Newton customers are picketing! What do you want to do? They’re angry,” Phil Schiller, then Apple’s chief marketing officer, warned during one of the most delicate moments of Steve Jobs’ return to the company as CEO. It was 1998, and Jobs was about to kill off a cult favorite: the Apple Newton.

The Newton was, in many ways, a forerunner to the iPhone—a product that would arrive nearly a decade after its death. Ending it was no easy decision. But where conflict with fans might have been expected, Jobs delivered a solution as unexpected as it was classic.

The Apple Newton Had to Go

After being ousted from Apple in 1985, Jobs founded NeXT, which Apple acquired in 1996—marking the beginning of his return. A year later, he became interim CEO, then permanent CEO until his retirement in 2011.

While Jobs is widely remembered for the iMac, iPod, iPhone and, to a lesser extent, the iPad, few recall that he also had to make tough calls—including killing off existing products. Some never made it to market. Others, like Newton, already had fans and momentum.

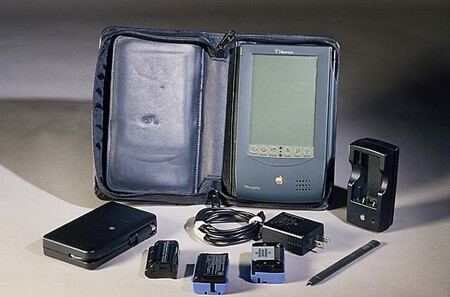

The Newton was a personal digital assistant launched in 1987, two years after Jobs’ initial departure. It sold just 200,000 units but built a loyal following. Inside Apple, some still believed in its future. Jobs didn’t. To him, the Newton was outdated and misaligned with the company’s new direction.

Within a year of returning, he pulled the plug: Newton’s development ended. Remaining inventory was removed from shelves. And fans were furious.

On Tim Cook’s First Day, Fans Showed Up to Protest

It took months for the public to react. But eventually, the backlash arrived in force. One seemingly ordinary day in 1998, a crowd of Newton loyalists appeared outside Apple’s Infinite Loop headquarters in Cupertino.

That same day, Tim Cook—Apple’s future CEO—was starting his first job at the company. Jobs had just recruited him from Compaq. As Cook approached the building, he had to cross a picket line.

“What did I do?” he recalled thinking, confused by the scene.

He rushed to tell Jobs, who responded with signature calm: “Oh yeah, don’t worry about that.” To Jobs, the protest was just another day at Apple—a company whose customers were deeply invested in its every move.

“We Love You, and We’re Sorry”

Schiller, now overseeing events and the App Store, remembered Jobs’ response as a lesson in marketing and empathy.

Jobs acknowledged the fans had “every right to be angry.” He praised the Newton, even while making it clear there was no going back. “We have to kill it,” he told Schiller. “And that’s no fun.”

Then came the directive: “Get them coffee and doughnuts. Tell them we love them and we’re sorry and we support them.”

So, Schiller did just that. The treats were handed out to the protesters. Slowly, tensions eased. Newton’s story faded into history. But Jobs’ gesture stuck.

A Tradition Was Born

That coffee-and-doughnuts moment became more than just a peace offering—it sparked a tradition. Today, when new iPhones launch, Apple Stores around the world often greet early-morning lines with refreshments. While online reservations are now standard, some fans still show up in person, and Apple still shows up for them.

It’s hard not to draw a line from that 1998 protest to today’s carefully cultivated Apple launch experiences. What started as damage control became part of the brand’s DNA.

Jobs’ response to Newton’s demise revealed a larger truth: Apple was willing to make hard decisions—but never at the cost of forgetting its most loyal supporters. That balance of boldness and empathy shaped not just Apple’s products, but its relationship with the people who believed in the company.

In that moment—quietly, over coffee and doughnuts—a new kind of Apple took shape. One that would change the way we think about technology, and the emotions we attach to it.

Images | James Mitchell | Jackie Alexander (Unsplash) | National Museum of American History Smithsonian Institution