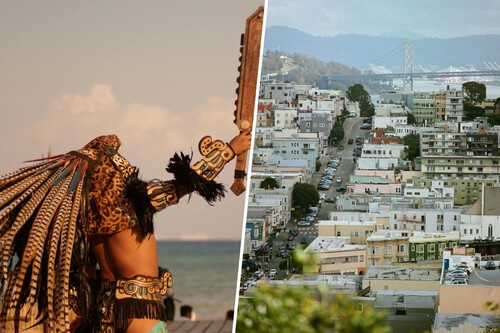

Destiny often has unexpected plans. Donald Trump’s second term has made immigration one of his administration’s top priorities. At the same time, Mayan languages are gaining ground and spreading across the U.S.—something few could have foreseen.

From Guatemala to Oakland. According to the BBC, Aroldo, a young man from San Juan Atitán, Guatemala, embarked on a four-month journey to California after his father died. He carried little more than his native language: Mam. This language, rooted in the ancient Mayan civilization, is one of many finding new life in the U.S. through Indigenous migration from Mexico and Central America.

Far from disappearing, Mayan languages such as Mam and K’iche’ are thriving across the border. They’re spoken in the streets and on the radio in areas like the San Francisco Bay Area. They are also among the most commonly heard languages in U.S. immigration courts.

An invisible community. History can be interpreted in many ways. One reading of this resurgence highlights a cultural complexity long ignored. The U.S. immigration system often classifies all migrants from Spanish-speaking countries as “Hispanic,” overlooking that many—like Aroldo and thousands more—don’t speak Spanish as a first language, or at all.

This broad classification erases the cultural, social, and linguistic distinctions among Latin American migrant communities. More importantly, it complicates the delivery of basic services. The BBC reports that researchers like Tessa Scott, a Mam linguist at the University of California, Berkeley, criticize the tendency to group all Guatemalans under one label. The result: miscommunication, a lack of qualified interpreters, legal confusion, and insufficient support for trauma—often the root cause of migration.

From ancestral languages to modern rights. The spread of Mayan languages isn’t only a product of migration but also a testament to cultural resilience. Today, more than 6 million people speak one of the 30-plus Mayan languages. The most widely spoken include Mam, K’iche’, Yucatec, and Q’eqchi’.

These languages descend from Proto-Maya, spoken before 2000 B.C., and are so distinct that a Mam speaker can’t understand K’iche’, and vice versa. Many survived colonization, the erasure of Mayan hieroglyphics during Spanish evangelization, and centuries of institutional neglect. Thanks to oral traditions and the colonial-era adoption of the Latin alphabet, Mayan languages endured—used in civil registries, wills, and community records that are still preserved in archives.

A living legacy. According to the BBC, some Mayan words have entered global usage. For instance, “cigar” comes from the Mayan word sikar, and “cacao” (the foundation of chocolate) also has Mayan roots and was introduced to Europe by Spanish friars such as Bartolomé de las Casas.

Although hieroglyphic writing was once eradicated for being “pagan,” it has been rediscovered in modern times. Since the late 20th century, American and Russian linguists—and more recently, Indigenous scholars—have worked to decode it. This revival has reignited appreciation for its sophistication and beauty. Today, groups like Ch’okwoj and Chíikulal Úuchben Ts’íib offer workshops and sell merchandise featuring ancient glyphs to engage new generations in their written heritage.

A growing diaspora. Mayan migration to the U.S. has reshaped both their home communities and their new ones. In places like San Juan Atitán, the economy has shifted from subsistence farming to dependence on remittances. “Migration is what sustains our village,” Silvia Lucrecia Carrillo Godínez, a Mam teacher, said in an interview with the BBC.

Migration has altered not only the economy but also community expectations. Learning basic math, picking up some Spanish, and heading to the U.S. have become common pathways to social mobility.

Transforming cities. In the Bay Area, Mayan communities initially settled in San Francisco’s Mission District. But as the cost of living soared, many moved to the East Bay—especially Oakland and Richmond. In San Juan, people often say that simply mentioning “I’m from Oakland” is enough for others to understand the context of migration.

There, amid the California fog, Aroldo and others have found a community bound by shared language and traditions. They take part in local festivals, receive Mam-language messages on WhatsApp, and dream of one day returning to build homes in their homeland.

Language as refuge. In a world where migration often involves profound loss, the persistence of Mayan languages represents cultural resistance. As the BBC illustrates through Aroldo’s story, Mam is more than a means of communication—it connects him to his childhood, family, and identity. In the home he shares with his cousins, he insists that his nephew, now in an English-speaking school, learn Mam first, then Spanish, and only then English.

As Aroldo puts it: “Language makes it harder to miss your land.” Mam, like other Mayan languages, isn’t a relic. It travels with him like a compass—a reminder of a living civilization reinventing itself in a place no one expected.

Image | Rodrigo Ortega | Kyle Ryan (Unsplash)