November 2024. Ukrainian forces were hunting a Russian drone different from the rest: a decoy drone designed to deceive and overwhelm enemy air defenses by simulating radar signals. That day, the surprise wasn’t so much that they had captured a specimen of the so-called Parody. The real surprise came when they opened it and discovered who had built that “Russian” machine. Curiously, the same thing has now happened with the latest missile in the conflict.

It wasn’t made in Moscow, but by the U.S. and a group of allies.

The ‘Russian’ Banderol missile. Ukraine has recently revealed the workings of the S8000 Banderol, a new Russian cruise missile developed by the Kronshtadt Group, known for its drones. Russia has deployed it in combat, representing a significant evolution in the Kremlin’s long-range attack strategy.

According to the Defense Intelligence of Ukraine (DIU), this missile is launched by Russian forces from nontraditional platforms such as Orion drones, similar in size to the U.S. MQ-1 Predator. Ukraine believes Russia may adapt it for Mi-28N attack helicopters. A small jet engine powers the Banderol, which has retractable wings and reaches 310 mph with a warhead weighing about 240 pounds. Its superior maneuverability suggests it could evade anti-aircraft defenses, making it a weapon of significant tactical value.

Made by “allies.” The DIU has examined several Banderol missiles in good condition after they were shot down or their remains recovered. Their technical analysis revealed a pattern that’s becoming increasingly common: Russia’s total dependence on foreign components, even for its most recent developments. In other words, the missile’s dissection reveals an amalgam of elements from countries that are supposedly Ukraine’s allies—and some that aren’t.

Dissection of the missile. The SW800Pro engine, manufactured by Chinese company Swiwin and available on platforms such as AliExpress, powers the rocket. The RFD900x telemetry module points to Australia. Batteries from Murata (Japan), Dynamixel MX-64AR servo mechanisms from Robotis (South Korea), and an inertial navigation system of possible Chinese origin complete the list.

According to the report, each missile contains around 20 microchips manufactured mainly in the U.S. but also in Switzerland, Japan, South Korea, and China. Many of these were purchased through the Chip and Dip network, one of Russia’s largest electronics distributors, currently under sanctions.

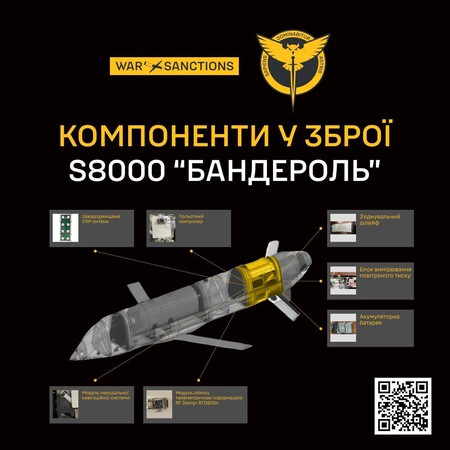

This infographic by the DIU shows the Banderol cruise missile and some of its foreign-made components.

This infographic by the DIU shows the Banderol cruise missile and some of its foreign-made components.

Sanctions evasion. The widespread presence of Western parts in Russian weapons isn’t new. The S-70 Okhotnik-B drone, gliding bombs and even weapons supplied by Iran and North Korea contain similar components. Despite hundreds of sanctions imposed by Washington and its allies on supplier companies, Russia has demonstrated a sophisticated ability to circumvent controls. It uses transshipment routes, third-country networks, and the largely unregulated market for recycled microelectronics, especially in China.

Many of these components come from civilian products, making them difficult to trace. According to The War Zone, Russian industry has perfected these evasion mechanisms over decades. The Semiconductor Industry Association has already warned that, despite efforts, “certain” actors continue to gain access to sensitive technology through deception.

Low-cost, long-range missile. The Banderol isn’t a high-end missile like the Kh-69, which carries warheads of up to 660 pounds. Still, it represents a low-cost solution with sufficient accuracy and medium range, optimized for the current conflict. The combination of its engine, guided by inertial navigation and satellite correction, with electronic countermeasure systems, makes it a key tool for saturation attacks or for hitting sensitive targets beyond the front line.

Although Ukraine doesn’t yet know if it can be reprogrammed in flight—which would be a valuable capability for mobile or opportunity targets—its mere existence is already a cause for concern. The country has suffered extensive damage from UMPK and UMPB gliding bombs, although the latter lack propulsion.

Russia and alternative platforms. The fact that the Banderol is designed to be launched from drones or helicopters represents an operational innovation in Russian doctrine. By not relying exclusively on strategic bombers or tactical fighters—frequent targets of Ukrainian air defense—Moscow can diversify its attack vectors, reduce risks and extend its ability to project force at a distance.

This frees up traditional aviation for other roles while multiplying the number of platforms capable of carrying out precision strikes. The concept also aligns with an emerging trend in the U.S.: the fusion of light cruise missiles and air-launched effect systems, which are cheaper, modular and adaptable to various missions.

Strategic implications. In short, the emergence of the Banderol is significant not only for what it represents on the military front, but also for what it reveals about technological dependence, the vulnerability of sanctions systems and tactical evolution.

According to the DIU, more than 4,000 foreign components have been identified in 150 Russian weapons analyzed, highlighting a structural failure in international export controls. In other words, the war in Ukraine is shaping the global arms industry and showing that modern conflicts are no longer fought with tanks and planes alone, but also with microchips, algorithms, and parts hidden in the heart of civilian devices.

This has also been intuited for centuries: In war, there are no “friends.”

Images | Vony Razom (Unsplash) | DIU