In January 1999, during the MacWorld Expo in San Francisco, then-Apple CEO Steve Jobs took the stage. The event featured an impressive demonstration of video games and highlighted how effectively they ran on Macs compared to their PC counterparts. However, Jobs made a controversial announcement that would go down in history when he introduced a PlayStation emulator.

Jobs aimed for every Mac to function as a PlayStation that could run games like Crash Bandicoot. This was made possible by tech company Connectix and its Virtual Game Station (VGS) software. At that time, Sony was thrilled with the success of its console and was shocked by what was being presented on such a big stage.

Turning Every Mac into a PlayStation

In 1998, the landscape of video games for the Mac was quite limited. PC gamers enjoyed classic adventures from LucasArts and other popular titles, including Warcraft, Diablo, and Age of Empires II. 1998 also marked the release of iconic games, such as StarCraft and Half-Life. The situation for Mac users was very different.

There were a few gaming projects, with companies like Bungie producing interesting titles such as Marathon. However, the dominance of PC gaming in the entertainment sector was clear. A young programmer named Aaron Giles had an exciting idea. If the Mac had a CD drive and the PlayStation used CDs, why not develop a way to play PlayStation games on a Mac?

Giles worked for Connectix. Founded in 1988, the company created pioneering software for the Mac. With each new version of Mac OS, Apple would often “borrow” the features developed by Connectix to include them in its own software. Apple would purchase shareware versions of similar concepts, avoiding direct dealings with Connectix.

Connectix not only focused on software but also created hardware. One creation was the Mac QuickCam, one of the first webcams ever made, which it sold to Logitech in 1998. However, emulation was the company’s main strength and the focus of many of its developers.

Giles began working on the project in 1998. Since Sony games could be played using a standard CD-ROM drive, he didn’t have to worry about the hardware component. The focus then shifted to emulating the BIOS and the PlayStation environment. By January 1999, the emulator was also ready.

On stage, Jobs announced the Virtual Game Station emulator to the world.

“Our goal is to have the best gaming machine in the world,” Jobs said while displaying an image of a PlayStation. “This is another game machine. It’s the most popular game machine in the world. Wouldn’t it be great if we could play some of those titles, too?” he added.

With that impactful statement, Jobs introduced Connectix’s product. He explained that Apple would sell the emulation software, which “turns your Mac into a Sony PlayStation,” for $49. This is less than half the cost of purchasing a new console.

Mind-Blowing

“It plays a few hundred of the Sony PlayStation games,” Jobs added as he introduced Phil Schiller, Apple’s VP of worldwide product marketing at the time.

Steve Jobs introduces Phil Schiller before playing Crash Bandicoot 3.

Steve Jobs introduces Phil Schiller before playing Crash Bandicoot 3.

“This is cool times 10. The ability to very quickly and very affordably take a Macintosh and run all the great PlayStation titles… and start to play them, is just a phenomenal idea,” Schiller said on stage.

He immediately began playing Crash Bandicoot 3. “This is the number one Sony PlayStation title shipping today,” Schiller pointed out. The game had only been released a few months earlier and was running at 100% speed on a Mac (with just a couple of minor glitches) by simply inserting the CD and launching VGS.

The big question was: How did it work?

Giles was able to successfully emulate a 33 MHz RISC processor on a 233 MHz iMac G3, despite the two being built on completely different architectures. What’s most impressive is that he accomplished this feat without using a single line of code from Sony.

Emulators recreate the hardware and software environment of a console on a different platform. In this case, Giles created a program that emulated a PlayStation on a Mac. The emulator acts as a real-time “translator” that converts game instructions meant for the console’s hardware into instructions suitable for the host device.

Emulating a console is resource-intensive because it involves doing double the work, but the most challenging aspect is emulating the BIOS. BIOS is the critical console software responsible for booting up the system and managing interactions between the hardware and the software.

To make his Virtual Game Station emulator function, Giles needed to replicate the PlayStation BIOS. He reached out to Sony for assistance with this. After receiving a refusal from the company and a cease-and-desist letter, he decided to take on an extraordinary challenge.

He meticulously researched the machine, studied the original BIOS, and rewrote it completely from scratch as his own version. This was an ambitious task, but it was also a stroke of genius. It left Sony with no legal recourse.

Sony Couldn’t Believe It

In 1999, Connectix released VGS for Mac, allowing most PlayStation games to run smoothly on Apple computers. Some features, like PlayStation controller vibration, didn’t work. Still, the software made a significant impact by giving Mac owners the equivalent of a PlayStation for just $49.

Game sales were likely to benefit from this innovation, given that it opened up a new market of potential users. However, Sony must have been furious. Not only had it lost control of its console, but Jobs had also praised the idea. In his blog, Giles recounts that at the booth Apple provided them at MacWorld, Connectix garnered considerable attention and sold a few hundred copies. In turn, it caught Sony’s eye.

The response from Sony was swift. Following the public presentation, the company launched a legal attack. Sony believed Connectix was infringing on its copyrights. It also found allies in companies such as Nintendo, SEGA, and 3DFX Interactive, which also had issues with Apple. Shortly after MacWorld, Sony took legal action.

On Jan. 27, 1999, the courts ruled against Connectix, preventing it from copying or using Sony’s BIOS code in the development of VGS. Additionally, the court ordered that it couldn’t sell the program in either Mac or Windows versions.

Connectix’s booth at MacWorld in 1999.

Connectix’s booth at MacWorld in 1999.

Additionally, unsold copies of the product were seized after the court ruled that Connectix could not use Sony’s BIOS. However, as previously mentioned, the BIOS in question wasn’t the original one created by Sony.

If You Can’t Beat Them, Join Them

Connectix appealed the decision, arguing in court that it had legally recreated the BIOS code through reverse engineering without copying Sony’s original code. As a result, the company wasn’t violating any of Sony’s protected code, and its emulator was protected under fair use.

This set a precedent in the world of emulation, although other companies, like Nintendo, have since attempted to challenge it. While emulators are legal for playing copies of games you own, it’s illegal to obtain those copies without consent.

In 1999, PlayStation was having a great moment. However, its life cycle was nearing an end, and Sony was set to release PlayStation 2 in 2000. The time that the Virtual Game Station spent out of circulation could have hurt Connectix. Still, before it could resume selling the software, Sony decided to make a deal and acquire the emulator’s license.

One More Thing…

What makes this so interesting is that Jobs himself, who would have been furious if this happened to him, presented a PlayStation emulator on a big international stage. The emulator itself demonstrated impressive performance and was an undeniable technical achievement. Additionally, this incident helped establish a legal framework for emulators in the U.S.

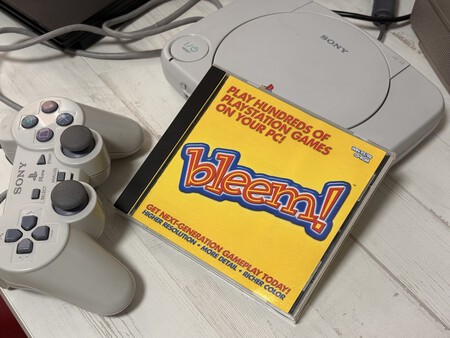

However, the story didn’t end there. While Sony was engaged in a legal battle with Connectix, another company was working on a similar emulator for Windows called Bleem!. Released in the early 2000s, Bleem! did more than simply emulate the PlayStation. It enhanced the graphics of Sony’s console on PC by using filters and offering better resolutions.

This created yet another headache for Sony. In response, the company sought to combat Bleem! by continuously suing its creators. Sony hoped that the ongoing legal battles would drain the Bleem! Company’s financial resources, and force it to abandon the project. In the end, this strategy was successful and Bleem! became a thing of the past.

On Apple’s side, Sony’s lawsuit against Connectix meant that Mac users were left without access to that sought-after PlayStation emulator. At the time, Jobs was probably satisfied with the thought of Bungie developing a game for Apple.

Little did he know that Microsoft was preparing to launch its first console, the Xbox. Microsoft ended up buying Bungie and “stealing” the game that had captured everyone’s attention at MacWorld in 1999: Halo.

Images | CARTIST | Aaron Giles

Related | You Can Now Install Windows on Your iPhone. The First Retro PC Emulator Has Arrived to iOS