Japan has a term for nearly everything that would require a full sentence to explain in English. The Japanese language has words to discuss the country’s demographic challenges and the reluctance of young people to attend school. The paradox of Tokyo’s growth while other areas decline also has a name. Other terms describe napping at work without fear of termination, and even the complex issue of men knocking women to the ground.

But, do the Japanese have a term for the trend of extravagant baby names? Soon, it won’t matter.

The end of creativity. The Japanese government is implementing new regulations to limit parents’ freedom in naming their children. The focus is on the pronunciation of kanji characters in the civil registry. This reform aims to address the rise of “kirakira names,” which are considered flashy or flamboyant. Since the 1990s, these creative names have led to confusion in administrative processes and, at times, teasing of children.

The use of kanji will still be permitted. However, parents will have to declare the phonetic reading of the name and adhere to officially recognized pronunciations to prevent unusual or controversial interpretations.

Response to linguistic chaos. The issue of unconventional names isn’t unique to Japan, but it’s become increasingly problematic there. This proliferation of uniquely read names poses challenges for schools, hospitals, and public services, particularly in a society that relies heavily on standardized digital records.

Some parents have taken their desire for originality to the extreme, choosing names such as Pikachu, Pokémon, Kitty, Naiki (which sounds like sports brand “Nike”), Pū (a nod to Winnie the Pooh), Ōjisama (“prince”), and even Akuma (“demon”). These choices have sparked social and institutional criticism. While the names often use legal kanji, their pronunciations are unprecedented, making them difficult to interpret.

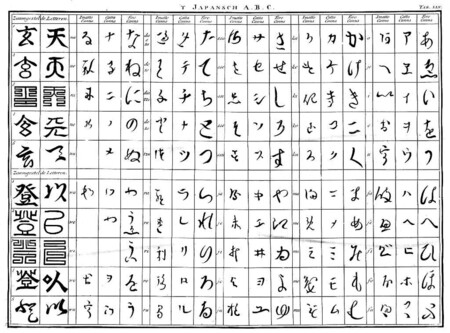

The Japanese alphabet.

The Japanese alphabet.

Tradition clashes. The new regulations aim to strike a balance between the desire for individuality and the weight of Japanese tradition, which generally favors homogeneity and social harmony. In a society where collective values greatly influence upbringing, many parents defend their choices as acts of self-expression against a backdrop of strong conformity.

Notable cases include that of Japanese politician Seiko Hashimoto, who named her children Girishia (Greece) and Torino (Turin) in homage to the Olympic Games. These instances highlight how even public figures can challenge traditional naming conventions, though they often face misunderstanding from their communities.

Pragmatic adjustments. Importantly, the law doesn’t aim to eliminate the variety of names but rather to organize language use. Among the approximately 3,000 kanji allowed, many have multiple accepted readings. However, some phonetic combinations have been so unusual that they’ve become unintelligible.

From now on, parents who choose unconventional pronunciations will need to justify their decisions in writing. If authorities find their choices unreasonable, they must propose a more understandable alternative. Officials have indicated that only the most extreme cases will be rejected, suggesting that they seek reasonable regulations rather than strict bans.

A significant change for Japan. The reform represents a rare modification of the country’s koseki. This is the legal record of the Japanese family unit and includes the names and birth dates of the head of the household, spouse, and children.

The new pronunciation criterion sets a precedent by regulating not only the written characters but also their readings. This change aims to protect the administrative and linguistic integrity of the system. In an increasingly digitized era, where data consistency is crucial, Japan has chosen to safeguard its system through language. This approach channels personal creativity while maintaining understandable and functional limits.

Images | Michael Rivera | itoldya_test1